FRIDAY MORNING MANNA

Biblical Numerology: NUMBER FIVE Part IV

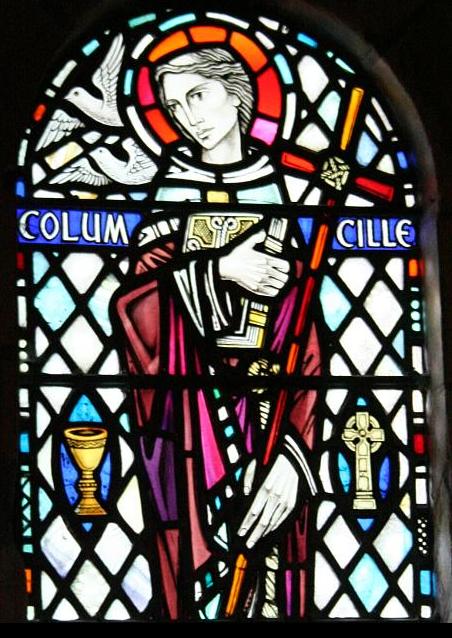

St. Columba of Ireland was a Sabbath-keeper

QUOTE OF THE WEEK:

“When religion is good, it will take care of itself; when it is not able to take care of itself, and God does not see fit to take care of it, so that it has to appeal to the civil power for support, it is evidence to my mind that its cause is a bad one.” –

“Letter to Dr. Price” by BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, sage of the Continental Congress

“Professor Andrew Lang says of them [churches set up or inspired by St. Patrick]:

‘They worked on Sunday, but kept Saturday in a Sabbatical manner.’ —‘A History of Scotland from the Roman Occupation,’ Vol. I, p. 96. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1900.

“Dr. A. Butler says of Columba:

‘Having continues his labors in Scotland thirty-four years, he clearly and openly foretold his death, and on Saturday, the ninth of June, said to his disciple Diermit: ‘This day is called the Sabbath, that is, the rest day, and such will it truly be to me; for it will put an end to my labors.’ —‘Butler’s Lives of the Saints,’ Vol. I, A.D. 597, art. ‘St. Columba,’ p. 762. New York: P. F. Collier.

“In a footnote to Blair’s translation of the Catholic historian Bellesheim, we read:

‘We seem to see here an allusion to the custom, observed in the early monastic Church of Ireland, of keeping the day of rest on Saturday, or the Sabbath.’ –‘History of the Catholic Church in Scotland,’ Vol. I, p. 86.

“Professor James C. Moffat, D.D., Professor of Church History at Princeton, says:

“It seems to have been customary in the Celtic churches of early times, in Ireland as well as Scotland, to keep Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, as a day of rest from labor. They obeyed the fourth commandment literally upon the seventh day of the week.’ —‘The Church in Scotland,’ p. 140. Philadelphia: 1882.

“But the Church of Rome could never allow the light of pure apostolic Christianity [in contrast to the “darkness of impure and corrupted apostolic Christianity,” the mother of which is the Romanized Papal Church headquartered in Rome!] to shine anywhere, for that would reveal her won religion to be apostasy. Pope Gregory I, in 596, sent the imperious monk Augustine, with forty other monks, to Britain. Dr. A Ebrard, says of this ‘mission’:

‘Gregory well knew that there existed in the British Isles, yea, in a part of the Roman dominion, a Christian church, and that his Roman messengers would come in contact with them. By sending these messengers, he was not only intent upon the conversion of the heathen, but from the very beginning he was also bent upon bringing this Irish-Scotch church, which had been hitherto been free from Rome, in subjection to the papal chair.’ –‘Bonifacius,’ p. 16. Guetersloh, 1882. (Quoted in Andrews’ ‘History of the Sabbath,’ fourth edition, revised and enlarged, p. 532).

“Through political influence, and with magnificent display, the Saxon king, Ethelbert of Kent, consented to receive the pope’s missionaries, and ‘Augustine baptized ten thousand pagans in one day’ by driving them in mass into the water. Then, relying on the support of the pope and the sword of the Saxons, Augustine summoned the leaders of the ancient Celtic church, and demanded of them: ‘Acknowledge the authority of the Bishop of Rome.’ These are the first words of the Papacy to the ancient Christians of Britain.’ They meekly replied: ‘ ‘The only submission we can render him is that which we owe to every Christian.’ ‘ —‘History of the Reformation,’ D’Aubigne, Book XVII, chap. 2.

“But as for further obedience, we know of none that he, whom you term the Pope, or Bishop of Bishops, can claim or demand.”–‘Early British History,’ G.H. Whalley, Esq. , M.P. p. 17 (Londodn: 1860): and ‘Variation of Popery,’ Rev. Samuel Edger, D.D., pp. 180-183, New York: 1849.

“Then in 601, when the British bishops finally refused to have any more to do with the haughty messenger of the pope, Augustine proudly threatened them with secular punishment. He said:

‘If you will not have peace from your brethren, you shall have war from your enemies: if you will not preach life to the Saxons, you shall receive death at their hands.’ Edelfred, king of Northumbria, at the instigation of Augustine, forthwith poured 50,000 men into the Vale Royal of Chester, the territory of Prince of Powys, under whose auspices the conference had been held.Twelve hundred British priests of the University of Bangor having come out to view the battle, Edelfred directed his forces against them as they stood clothed in their white vestments and totally unarmed, watching the progress of the battle—they were massacred to a man. Advancing the university itself, he put to death every priest and student therein, and destroyed by fire the halls, colleges, and churches of the university itself; thereby fulfilling, according to the words of the great Saxon authority called the Pious Bede, the prediction, as he terms it, of the blessed Augustine. The ashes of this noble monastery; its libraries, the collection of ages, having been wholly consumed.’ –‘Early British History,’ G. H. Whalley, Esq., M.P., p. 18. London: 1860. See also ‘Six Old English Chronicles,’ pp. 275, 276; edited by J.A. Giles, D. C. L. London: 1906.

“D’Aubigne says of Augustine: ‘A national tradition among the Welsh for many ages pointed to him as the instigator of this cowardly butchery. Thus did Rome loose the savage Pagan against the primitive church of Britain.’ —‘History of the Reformation,’ D’Aubigne, book 17, chap. 2.

“This was the master stroke of Rome, and a great blow to the native Christians. With their university, their colleges, their teaching priests, and their ancient manuscripts gone, the Britons were greatly handicapped in their struggles against the ceaseless aggression of Rome. Still they continued the struggle for more than five hundred years longer, till, finally, in the year 1069, Malcom, the King of Scotland, married the Saxon princess, Margaret, who, being and ardent Catholic, began at once to Romanize the primitive church, holding long conferences with its leaders. She was assisted by her husband, and by prominent Catholic officials. Prof. Andrew lan says:

‘The Scottish Church, then, when malcom wedded the sainted English Margaret, was Celtic, and presented peculiarities odious to the English lady, strongly attached to the establishment as she knew it at home . . . The Celtic priests must have disliked the interference of an Englishwoman.

‘First, there was a difference in keeping Lent. The Kelts [spelling in the original] did not begin it on Ash Wednesday . . . . They worked on Sunday, but kept Saturday in a sabbatical manner.’ –‘History of Scotland,’ Vol. I, p. 96.

“William Skene says:

‘Her next point was that they did not duly reverence the Lord’s day, but in this latter instance they seem to have followed a custom of which we find traces in early Monastic Church of Ireland, by which they held Saturday to be the Sabbath on which they rested from all their labors.’ – ‘Celtic Scotland,’ Vol. II, p. 349. Edinburgh: David Douglas, printer, 1877.

‘They held that Saturday was properly the Sabbath on which they abstained from work.’—Id., p. 350.

‘They were wont also to neglect the due observance of the Lord’s day, prosecuting their worldly labors on that as on other days, where she likewise showed, by both argument and authority, was unlawful.’ — Id., p. 348.

SCOTLAND UNDER QUEEN MARGARET

“Professor Andrew Lang relates the same fact thus:

‘ . . . They worked on Sunday, but kept Saturday in a Sabbatical manner . . . These things Margaret abolished.’ —‘A History of Scotland from the Roman Occupation,’ Vol. I, p. 96. New York: Dodd, Mead, and Co., 1900.

“The Catholic historian, Bellesheim, says of Margaret:

‘The queen further protested against the prevailing abuse of Sunday desecration. ‘Let us,’ she said, ‘venerate the Lord day, in as much as upon it our Savior rose from the dead: let us do no servile work on that day’ The Scots in this matter had no doubt kept up the traditional [that is, the Biblical’] practice of the ancient monastic Church of Ireland which observed Saturday, rather than Sunday, as a day of rest.’—‘History of the Catholic Church in Scotland,’ Vol. I, pp. 249, 250.

“Finally the queen, the king, and three Roman Catholic dignitaries held a three-day council with the leaders of the Celtic Church. Turgot, the queen’s confessor, says:

‘It was another custom of theirs to neglect the reverence due to the Lord’s Day, by devoting themselves to every kind of worldly business upon it, just as they did upon other days. That this was contrary to the law, she proved them as well by reason as by authority. ‘Let us venerate the Lord’s Day, said she, ‘because the resurrection of the Lord, which happened upon that day, and let us no longer do servile works upon it; bearing in mind that upon this day we were redeemed from the slavery of the devil. The blessed Pope Gregory affirms the same saying, ‘We must cease from earthly labor upon the Lord’s Day.’“ . . . From that time forward . . . no one dared on these days either to carry any burdens himself or to compel another to do so.’ —‘Life of Queen Margaret,’ Turgot, Section 20; cited in ‘Source Book,; p. 506, ed. 1922.

“Thus Rome triumphed at last in Scotland. In Ireland also the Sabbath-keeping churchestablished by Patrick was not left long in peace:

‘Giraldus Cambrensis informs us that in the year 1155 Henry II, King of England, was entrusted by Pope Adrian IV with the mission of invading Ireland with devastating was to extend the boundaries of the Church, so that even the Irish would become faithful to the Church of Rome.’ The Pope wrote Henry:

‘’ You, our beloved son in Christ, have signified to us your desire of invading Ireland, . . . and that you are also willing to pay to St. Peter the annual sum of one penny for every house. We therefore grant a willing assent to your petition, and that the boundaries of the Church may be extended, . . . permit you to enter the island.’ ‘ Ecclesiastical Records of England, Ireland, and Scotland,’ Rev. Richard Hart, B.A., pp. xv, xvi.

“Thus we see that in Scotland an English queen ‘introduced changes which, In Ireland, came in the wake of conquest, and the sword. For example, the ecclesiastical novelties which St. Margaret’s influence gently thrust [?] upon Scotland, were accepted in Ireland by the Synod of Cashel (1172) under Henry II. Yet there remained, in the Irish Church, a Celtic and an Anglo-Norman party, ‘which hated one another with as perfect a hatred as if they rejoiced in the designation of Protestant and Papist.’ ‘ — History of Scotland, Andrew Lang, Vol. I, p. 97.

“But whether this triumph of Catholicism over the native Celtic faith was accomplished by the devastating wars of Henry II, or by Queen Margaret’s appeal to Pope Gregory, and her threat of civil law, in either case it lacked an appeal to plain Bible facts, accompanied by the convicting power of the Holy Spirit. And while the leaders of the Celtic Church might reluctantly yield to the civil authorities, the people, who had kept the Bible Sabbath for centuries, requested divine authority for Sunday-keeping. For some time the papal missionaries, who preached this strange gospel to the Britons, fabricated all kinds of stories about miraculous punishments that had befallen those who had worked on Sunday: Bread baked on Sunday, when it was cut, sent forth a flow of blood; a man plowing on Sunday, when cleaning his plow with an iron, had it grow fast to his hand, so that he had to carry it around to his shame for two years.” – Facts of Faith, Christian Edwardson, (Revised ed), “Celtic Sabbath-Keepers,chap., pp. 137-143. Southern Publishing Asso., Nashville, TN . 1943. (To be continued next week).